learn how

Ancient Techniques - Textiles - Construction

Before the Spanish conquest, clothing was commonly made on the backstrap loom, which continues to be used today. Textiles produced were finished on all four sides; they were woven to size and were not cut. Yarn was prepared by spinning and plying the fibres.

Archaeological examples of pre-Hispanic weaving in the Americas confirm a high level of attention to detail, with sophisticated texture and patterning.

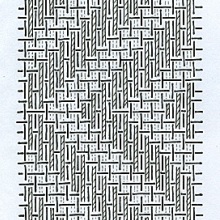

The supplementary warp technique is a way of introducing warp patterning into a woven fabric, by floating extra warps over the plain weave ground, without disturbing the basic structure of the weave. The supplementary warps are interlaced regularly with the weft between the ground warps as inserts, and floated on the back in other areas.

Supplementary weft technique creates a design by floating extra wefts over the ground weave, without disturbing the structure of the weave. Wefts are inserted along the same passage as the main weft, and then worked backwards and forwards to create the design. This is carried out on the loom, and called brocading. The decorative weft can change colour in each row, resulting in a variety of colours throughout the design. The ground is usually a plain cotton weave. South American supplementary weft yarns are frequently wool, while in Central America, cotton is used for the supplementary weft yarns.

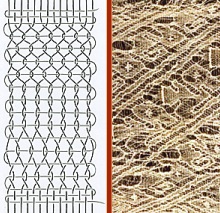

Gauze weave is created when two or four warp yarns cross each other, and the crosses are held in place with a weft yarn. The warp yarns then re-cross to their original position, producing the effect of small holes in the fabric. These gauzes were ordinarily made with a cotton yarn, usually over-twisted to give the fabric a crepe-like appearance. The Chancay textile pictured left, woven c. A.D. 1200-1550, is a fine example of ancient gauze weave.

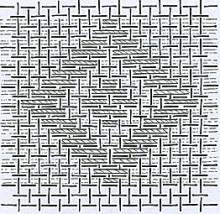

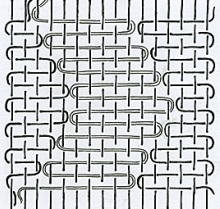

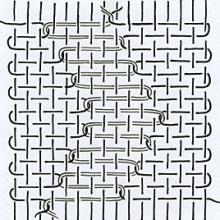

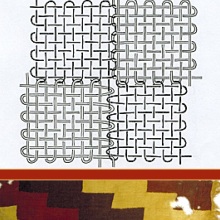

Complementary Warp

Warps of two different colours are set up in two complementary sets that are integral to the structure of the fabric. Unlike supplementary weft, there is no ground cloth on top of which the pattern is created. Each warp has its counterpart on the opposite face of the cloth, and the design is achieved from the two sets of warps interlacing with the weft. The result is a design with the colours in reverse on each face.

Tapestry is a simple structure, in which warp yarns were covered with weft yarns, and the changes in colours of the weft yarns created the design. Peruvian tapestry almost always uses a cotton warp covered by a wool weft.

Slit Tapestry - The wefts do not interlock at the intersection of adjacent colour areas. It is associated with the northern and central coastal cultures of Chimú, Lambayeque and Chancay.

Interlocked Tapestry - The wefts of adjacent colour areas form an interlocking join. It is characteristic of the cultures of the southern highlands, Wari and Inka, who used interlocked tapestry to create their high prestige textiles.

Dovetailing - Wefts of different colours turn around a single warp, singly or in pairs of threes at the intersection of adjacent colour areas. It is found on the central coast of Peru.

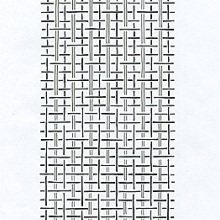

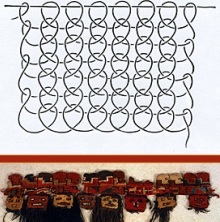

Cross-knit Looping - In this Peruvian stitch, a loop is formed that is closed by the crossing of the yarn, which passes back over itself. It is done with a single needle. Despite this structural difference, the completed network resembles knitting.

The fragment pictured left was stitched by a Nasca weaver some 1,800 years ago. Representing severed heads, they once adorned a man's garment.

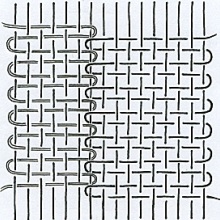

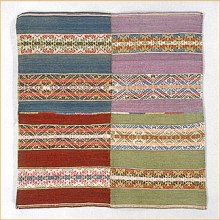

Discontinuous Warp and Weft - Here the warp and weft yarns do not pass from selvedge to selvedge. Instead, they cross their own colour area, and then make a U-turn where one colour meets the other colour and the colour changes. Both warp and weft are discontinuous, which is structurally a very difficult fabric to produce, and this technique does not occur anywhere in the world outside of Peru.

The example pictured left was woven c. A.D. 1300-1550 in the southern highlands of Peru by a non-Inka group (T94.1013).

Most ancient fabrics in Central and South America were woven on a simple backstrap loom, of a type still in use throughout these areas. Other looms used in Peru were the vertical frame loom, and the horizontal loom fixed to the ground with stakes. Here a weaver from Chinchero, a village in the southern highlands of Peru near Cusco, weaves with naturally dyed yarn on a backstrap loom.

The width of the fabric woven on the backstrap loom does not exceed the distance across which the weaver could pass a shuttle from hand to hand (usually about 60-75 cm). Two pieces of this uncut width with four selvedges could be sewn together to produce a larger cloth. Beginning at one end of the loom, the fabric was woven a short distance, then the loom was turned and the weaving started at the other end. As the warp was filled, the shed rod and heddles became ineffective, and the final weft insertion had to be done with a needle.

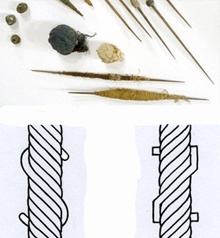

In Mexico and Central and South America, spindles of thorn and wood, with or without spindle whorls of pottery, stone or wood, were used for spinning fibres. Today wool is spun with a drop spindle, and cotton with one end of the spindle resting in a small bowl. It is likely these practices were in use before the Conquest.

While spinning, fibres are twisted to either the left or right, resulting in a spiral that resembles either the letter S or Z. Single yarns are usually plied together. This produces a stronger thread, with the ply in the opposite direction to the twist. The direction of the spin and twist of cotton varies, and can be an important indicator of the provenance of certain textiles in Peru.