learn how

Traditional Weaver - Nilda Callañaupa Alvarez - A Weaver's Story

The weaving tradition of the Inka people - and of those who lived before them - has continued in some areas of Peru. In fact, many techniques and designs that exist today have survived two thousand years of being handed down from older to younger weavers. However, when Nilda was growing up in Chinchero during the 1970s, she saw that traditional weaving had begun to disappear. Nilda recalls, "Nobody my age was putting their attention to traditional things, only the elders (like Nilda's mother Guadelupe, pictured left). Everybody was using acrylic for the tourist market and making very simple designs...belts, bags, narrow pieces, cheap things, $1 or $2 a piece."

When Nilda left her home in Chinchero to attend school in Cusco, she took her spindle with her. She went on to study textile history in the United States and earned a graduate degree from a Tourism Program in the Cusco area. Throughout, her love for her weaving stayed with her, and her desire to revive the practices of traditional Peruvian textiles prompted her to start working with the weavers in Chinchero. She founded the Center for Traditional Textiles of Cusco (CTTC) in 1996.

Image: © David VanBuskirk, www.incas.org

Through the work of the Center, Nilda and others are dedicated to helping Inkan textile traditions survive, and to providing support to weaving communities. Currently the CTTC is working with several communities and over 200 weavers, encouraging the use of hand-spun wool, natural dyes and the revival of traditional techniques and designs. Nilda visits her communities on a regular basis (seen here at Chahuaytiri) and buys textiles for the Center. She has helped the weavers to set up their own organization with a President and a Board to oversee the project. Every weaver must give a percentage of their earnings to the Board, to form a reserve fund to help those in need.

Andean peoples have always drawn materials from their environment in order to survive in their harsh mountainous landscape. For thousands of years, clothing for warmth and protection has been fashioned from animal fibres. Before the conquering Spanish arrived, highland peoples herded llamas and alpacas (seen grazing here), using their wool for weaving cloth, braiding ropes, and other needs. Today these practices continue in some areas. Sheep, which were introduced to the highlands by the Spanish in the 1500s, are also raised. Sheep's wool is used for making cloth as well as knitting.

Nilda learned to spin at the age of seven as she worked in the mountains looking after her family's sheep. Spinning is one of several stages in the preparation of wool for weaving or knitting. The preparation process includes the gathering of wool, and its spinning, plying and dyeing.

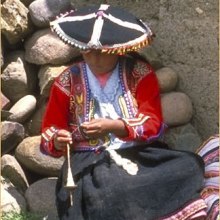

While in the mountains, Nilda and other girls were given pieces of wool from the backs of animals (where the hair is shorter and coarser). The best yarn was reserved for the older, experienced weavers who taught the girls (like this youngster from Chinchero) to spin and weave.

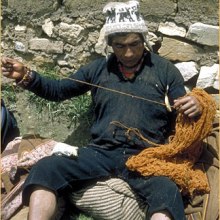

After Nilda's first spinning as a seven year old child, she gave her wool to her mother. "The first year my mother took my spinning to the river to be washed, as is the tradition of our ancestors" Nilda tells us. When Nilda spins today, as is the tradition in the Cusco area, she takes alpaca wool that is unwashed. She draws strands from a pile of raw wool, and using a drop spindle, spins the wool in a Z or clockwise direction. It takes seven to eight hours to spin a full spindle. According to Nilda, "practice and good wool" makes a good spinner. Pictured here is a young spinner from Pitumarca.

In some communities near Cusco, only the women spin. In Chahuaytiri, the women spin for their husbands who weave. In Aacha Alta, both the men and women spin.

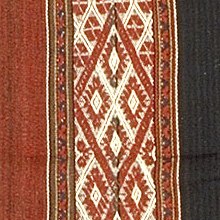

Yarn is occasionally spun in the opposite direction, or counterspun. This S-spun, Z-plied yarn is called lloq 'e, or "left-handed" by Quechuan speakers. Some say it has a magical quality. Weavers in Chahuaytiri lay groups of counterspun yarns next to each other in the ground cloth as shown in this image. This is believed to impart a protective quality to the cloth by counteracting negative energy and bestowing balance. These cloths were to be worn by pregnant women and others needing protection.

In the next stage of yarn preparation, Nilda would take the yarn from two spindles of spun wool, and wrap the two yarns into a ball ready to be plied. Yarn is always 2-ply to make it strong for the tension required on a backstrap loom. The ball is then wound into a skein for washing and dyeing. Afterwards, the two yarns are plied together by twisting them in the opposite direction to the original spinning (or in the S-spun, or counter-clockwise direction). When Nilda is plying wool she says it should be "twisted as fast as you can". The weaver pictured left is preparing dyed skeins for plying at Chahuaytiri.

When Nilda went to school in Cusco, she took her spindle with her. She explains, "I always brought my spindle. That's the easiest thing to bring. You need yarn, you have to produce yarn, you cannot just be a weaver. (My spinning) is the thing I am most proud of today. I was getting good grades, I could have easily dropped my spinning and my textiles. I think emotionally it is from the heart, in your life things happen that you can't explain. I just love it...it is something I like to do. The teachers didn't understand why I was interested in it, so a lot of times I just didn't talk about it."

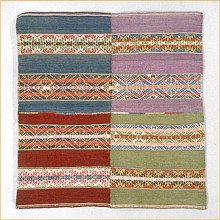

When Nilda is ready to weave, she uses a backstrap loom, a series of shaped sticks and ties on which a continuous warp and string heddles are used to produce a cloth with four finished edges. Weavers in the Cusco area attach the loom to a belt they wear, and tie the other end to an immovable object. They also use a four-staked loom. Backstrap weaving using a variety of techniques and designs can produce elaborately patterned cloth.

Backstrap Loom

Most ancient fabrics in Central and South America were woven on a simple backstrap loom, of a type still in use throughout these areas. Other looms used in Peru were the vertical frame loom, and the horizontal loom fixed to the ground with stakes. Here a weaver from Chinchero, a village in the southern highlands of Peru near Cusco, weaves with naturally dyed yarn on a backstrap loom.

The width of the fabric woven on the backstrap loom does not exceed the distance across which the weaver could pass a shuttle from hand to hand (usually about 60-75 cm). Two pieces of this uncut width with four selvedges could be sewn together to produce a larger cloth. Beginning at one end of the loom, the fabric was woven a short distance, then the loom was turned and the weaving started at the other end. As the warp was filled, the shed rod and heddles became ineffective, and the final weft insertion had to be done with a needle.

Natural dyes have been used in Andean hand-woven textiles since ancient times. In the second half of the nineteenth century, cheap chemical dyes became available and were widely used by Andean weavers. As a result, much of the indigenous dye tradition was lost. Currently, Nilda encourages weavers to use dyes from local plants and flowers, as was practiced in the past. She says this is "because our ancestors did...We are trying to do as they did." Here we see members of Nilda's family dyeing yarn naturally in Chinchero.

Nilda's work with natural dyeing has not been without challenges. "There are many problems, wood problems, boiling time, getting supplies they need." It is much more expensive and labour-intensive to use natural dyes.

In the long term, Nilda feels the many benefits of natural dyeing will far outweigh the difficulties. For example, natural dyes are safe for the environment, and do not pollute the soil when discarded (unlike chemical dyes). These benefits encourage Nilda and the weavers. They want to make their communities safer for the children who play nearby; one day, the elders will pass on their wisdom to these children.

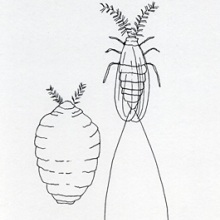

COCHINEAL (Dactylopius coccus) - A brilliant red dye is produced from cochineal insects, which feed on the prickly pear cactus (Opuntia) - in particular, the species called nopal. The insects manufacture a rich maroon pigment and they store this pigment in body fluids and tissues. The dye properties of cochineal were discovered by ancient indigenous groups who would dry the female insects in the sun, and then grind the bodies to produce a powder. Depending on the mordant used, dyers could achieve not only beautiful crimsons and pinks, but also near-black and even purple shades. To produce one pound of cochineal powder, it took 70,000 dried insects. An acre planted with nopal cacti yielded 100 to 150 kg of cochineal powder.

In very ancient times in Peru, red dye may have come from the plants Relbunium hypocarpium (known as antanco or chamiri) and Relbunium microphyllum (chapichap). These plants are still found in the high valleys of present-day Peru. In later times (c. 400 B.C.-A.D.500), red was also obtained from the female cochineal insect, which lives on the nopal cactus. By the time of the Inka, cochineal was the most widely used red dye. Today, natural dyeing with cochineal is fairly expensive for weavers. Using cochineal to produce red costs about eight times more than commercial red dye.