Identity& Society

Textiles convey messages about individuals and groups of people. Images, patterns, colours, materials, and ways of making suggest belonging and kinship, social connections, and deep understanding of individuals, cultures, and subcultures. Textiles shape us as much as we shape them; they can conceal us and they can make us visible.

For the first theme of the Social Being online programs, exhibition curatorial consultant Nakasuk Alariaq traces the roots of contemporary art in her hometown of Sikusiilaq or Kinngait and shares personal anecdotes on the artists featured in Printed Textiles from Kinngait Studios.

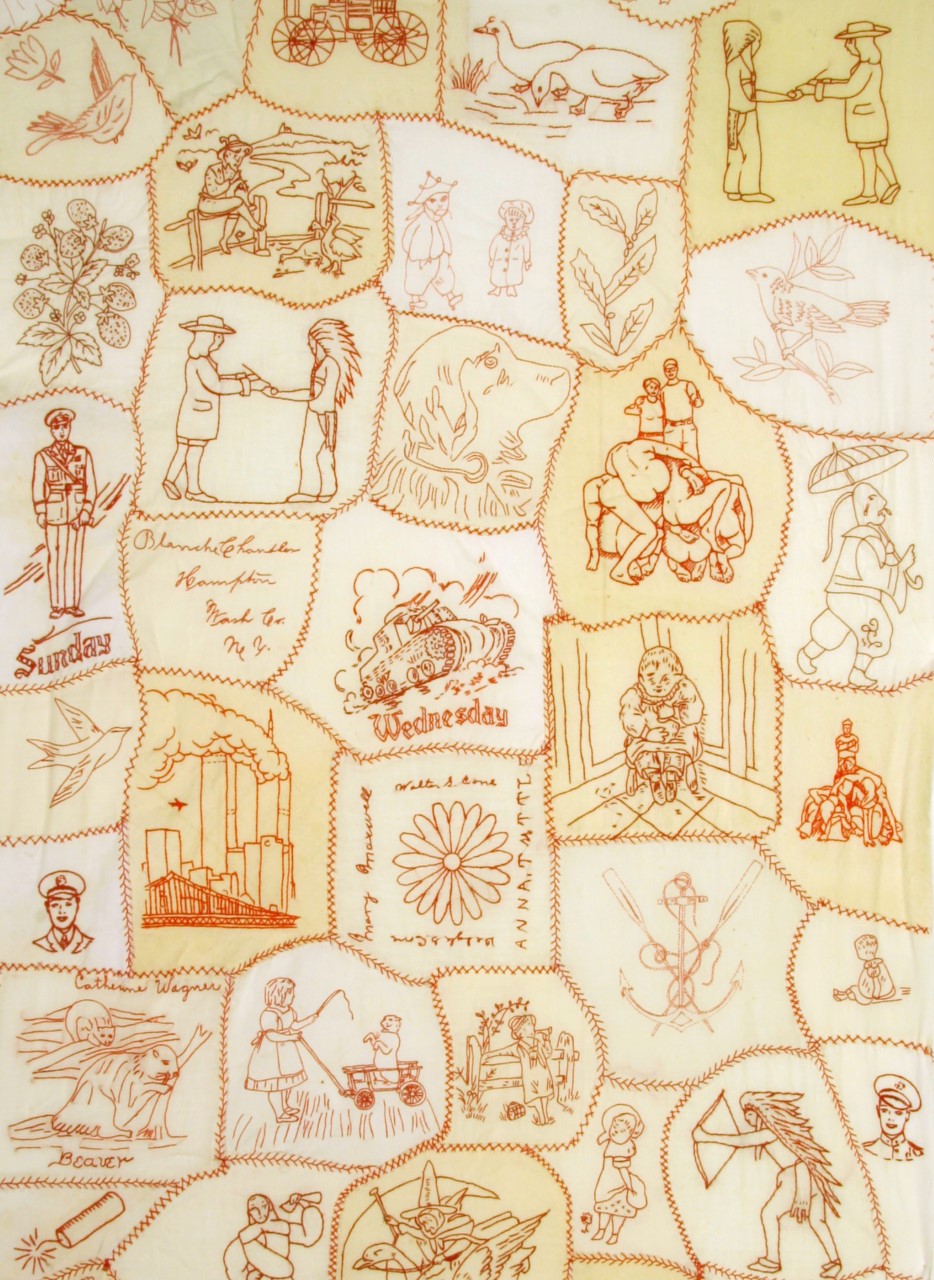

Artists Catherine Heard and Shiemara Hogarth lead an online sewing circle to embroider patches for Catherine’s project Redwork: The Emperor of Atlantis, where participants are encouraged to engage in dialogue and idea exchange. Participants share the stories behind their chosen images and shed light on the personal and political context of those stories.

Program participant Kate chooses images of two prominent political figures’ falling statues. Kate’s third image is of a pregnant woman with a thunderbolt sign on her belly, fighting for her reproductive rights. Kate connects the three pieces to the contemporary Polish women’s movement. Jenny’s image speaks to her experience during the anti-Vietnam war movement in the U.S. and her immigration to Canada. Barbara’s image tells a personal story of child abuse by a parent whose embroidery work speaks to his delicate side as a little boy. And Angela’s angel piece speaks to her ties to the Black Lives Matter movement that aims to highlight the non-profit volunteer-run group of Guardian Angels, founded in 1979, USA.

Alexa Hatanaka and Flora Shum introduce us to artists from Kinngait, Parr Josephe, and Ashoona Ashoona. In the video Gyotako Printmaking with Parr, he demonstrates this printmaking tradition that was used to physically record the size of a fishing catch.

Kinngarni Katujjiqatigiit Collaborator: Ashoona Ashoona demonstrates parts of his stone carving process for the print designed by Alexa Hatanaka. Ashoona highlights his generational connections and familial ties to many artists from Kinngait while expressing his passion for passing on his knowledge to the younger generations in the community.

Lastly for this theme, in Collection Spotlight: Prayer Rug Defne Inceoglu, MMSt, Curator and Artist talks about one of their favourite pieces in the museum collection. Defne was our intern in the public engagement and communications department in 2019-2020.

↓ Image | Prayer Rug, Turkey, mid 20th century; cotton; velour, machine woven; 104 x 64 cm; T88.0001

01. Programs

Online Presentation: Printed Textiles from Kinngait Studios tour with Nakasuk Alariaq

On Saturday April 17, exhibition curatorial consultant Nakasuk Alariaq traced the roots of contemporary art in her hometown of Sikusiilaq or Kinngait and shared personal anecdotes on the artists featured in Printed Textiles from Kinngait Studios. Nakasuk Alariaq is an Inuk-Finnish Canadian who was raised in Sikusiilaq (Kinngait/Cape Dorset). She has completed her Master’s in Art History and Curatorial Studies at Western University where she focused her thesis on Inuit self-representation in arts institutions.

Online Workshop: Embroidery Sewing Circle with Catherine Heard and Shiemara Hogarth

On Sunday May 9, Heard and textile artist Shiemara Hogarth lead an online sewing circle to embroider patches for Redwork: The Emperor of Atlantis, and participants were encouraged to engage in dialogue and idea exchange. This program is the second of two programs featuring Redwork: The Emperor of Atlantis and is in partnership between the Art Gallery of Windsor, the Niagara Artist Centre, and the Textile Museum of Canada.

02. MORE ON THIS THEME

Kinngarni Katujjiqatigiit Collaborators

Kinngarni Katujjiqatigiit / ~ ᑭᙵᕐᓂ ᑲᑐᔾᔨᖃᑎᒌᑦ is an ad-hoc collective of professional artists living and/or working in Kinngait, NU, textile artist—Ooloosie Ashevak, Elder, sewer, and traditional knowledge-keeper—Nicotye Qimirpik, emerging artist—Cie Taqiasuk, land and cultural carrier—Sarah Oshutsiaq, printmaker and artist—Ashoona Ashoona, and Toronto-based visual artists—Alexa Hatanaka and Flora Shum (all but Alexa and Flora are Kinngarmuit). Kinngarni Katujjiqatigiit designs and implements youth-focused programmes and curriculum for the Peter Pitseolak Studio, in collaboration with our stakeholders: Kinngait District Education Authority (DEA—community elected Elders and youth advocates) and Peter Pitseolak School. KC embodies Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit traditions and methodologies within our artistic practice and community relations. KC is made possible with the support of Canada Council for the Arts, and project-based support from: British Museum, TakingItGlobal, Government of Nunavut, Toronto Biennial of Art, Canada Goose, The Japanese Paper Place, Paperhouse Studio, Indigenous Services Canada and Qikiqtani Inuit Association.

Parr Josephee is from Kinngait, Nunavut. He is the namesake of one of the first and most prolific graphic artists from Kinngait, his great-grandfather Parr Parr. He is also the son of the renowned, innovative carver Isacci Etidloie. In 2015, Josephee collaborated with three other young Kinngait artists and Embassy of Imagination (EOI) on the unprecedented 50’ mural Piliriqatigiingniq in Toronto during the Pan Am Games, and had since collaborated on several monumental public mural projects. Josephee also represented Kinngait on the 2015 Students on Ice expedition to Greenland. Parr graduated from Oasis Skateboard Factory in 2017 and attended Nunavut Sivuniksavut. He is a mentor to other young Inuit artists. Parr continues to carry forward what his ancestors began, a celebrated cultural tradition and distinctive contemporary art form.

Ashoona Ashoona is a multidisciplinary artist based in Kinngait, NU who works as a carver, printmaker and graphic artist. Born to an artistic family, Ashoona learned to carve by watching and copying his father Koomwartok Ashoona and became a full-time artist at age 22, making carvings from locally quarried stones. Through his work, Ashoona intentionally continues the legacy of his Grandmother Pitseolak Ashoona and his Uncle Kiugak Ashoona.

Ashoona started as a stonecut printmaker in 2012 and continues to work as a master printer in the famous Kinngait studios producing works in collaboration with Kinngait artists such as Quvianaqtuk Pudlat, Ningiukulu Teevee, Tim Pitsiulak, and Kenojuak Ashevak, as the last print work produced by the late, treasured artist. Ashoona both carves the stonecut blocks and prints the work.

Ashoona was part of the team who built a collaborative work for the Inuit Circumpolar Council meeting in 2014, as part of York University’s “Mobilizing Inuit Cultural Heritage.” Ashoona has contributed as a printmaker and youth facilitator to community-engaged projects such as “Atigiit, Silapaat” (2019-2020) for The British Museum’s exhibition “Arctic: Culture and Climate.” He is co-leading Ryerson University’s first public art project in 2021 as part of curator Gerald McMaster’s project “Arctic Amazon.”

Collection Spotlight: Prayer Rug

“Growing up in a Turkish household, rugs and prayer rugs were very common in our home and in the homes of our friends and family. Rugs held a dual meaning for my family, being both decorative and sacred. We were able to walk freely across the rugs that spread out over the floors of our home without a second thought. However, the prayer rugs which belonged to my anneanne (grandmother), were not to be touched when not in use for prayer. Prayer rugs are, by their namesake, used during prayer, which we call namaz in Turkey.

Prayer rugs function as a part of abdest (as we say in Turkish), or Wuḍū, the ritual cleansing and purification of parts of the body. Once abdest is completed, prayer rugs are used to maintain cleanliness between the person and the ground.

The rug from the Museum’s collection was created sometime in the early 20th century. It has a beautiful representation of the Kaaba in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. While in use, this rug would have been directed physically towards Mecca itself; for example, on the North American continent, we pray eastward. To parallel, the photo is an image of me as a child in the 90s, posed on one of my grandmother’s prayer rugs. Like the one in the Museum’s collection, my grandmother’s also had an image of the Kaaba. The Kaaba is a holy building at the center of the Masjid al-Haram, the most important mosque for those who practice Islam. This mosque is located in Mecca, Saudi Arabia.

Islamic objects are often adorned with geometric patterns; representations of ornate floral designs and religious script with a strong eye for symmetry. Even across millennia, these familiar motifs appear again and again in Islamic art; a representation of the intricate relationship between all living things. Islamic art inspired me to study the history of art and the museums who care for these objects – projecting me into my career today”.

Defne Inceoglu, MMSt, Curator and Artist